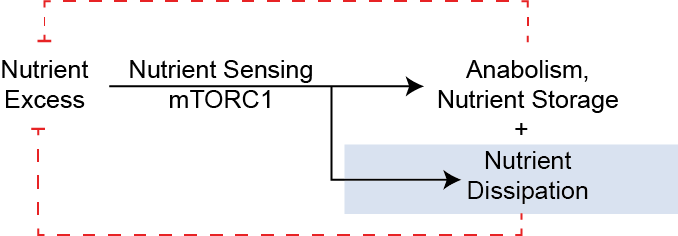

The obesity pandemic is a leading cause of ill health, and is a risk factor for many chronic diseases including diabetes, liver disease and cardiovascular disease. While most approved anti-obesity therapies focus on reducing energy intake, the other way to promote negative energy balance is to elevate energy expenditure and nutrient dissipation. But how is nutritional status sensed? In one framing, the center of nutrient sensing is the protein kinase complex mTORC1. While mTORC1 is widely appreciated to mediate nutrient storage, I think of mTORC1 as responding to nutrient and energy excess by engaging both anabolic and catabolic pathways.

First lets consider the counterfactual, that mTORC1 promotes primarily anabolic pathways, what might we expect from that framing:

- Increased triglyceride storage in tissues with activated mTORC1. This could include adipose and liver tissues.

- Nutrient absorption might be increased, for example mTORC1 could promote gastrointestinal transport to more efficiently absorb nutrients when activated.

- Overall increased nutrient storage in models with activated mTORC1, and reduced in conditions of reduced mTORC1 activity. This could be due to positive energy balance (e.g. by reduced energy expenditure and/or increased appetite).

As I describe below, none of this occurs.

Physiological processes governed by mTORC1: A Dual-Flux Model of Anabolism and Catabolism

The anabolic roles of mTORC1 are very well established (See 1 for a review). These include promoting:

- Protein synthesis: particularly protein translation via 4EBP phosphorylation, S6K-dependent eIF4B phosphorylation, and eEF2-kinase phosphorylation and activation. mTORC1 also enhances ribosome biogenesis via both promoting rRNA transcription and translation of ribosomal mRNAs. mTORC1 also enhances m^6^A‑dependent post‑transcriptional control. This selectively increases the translation and stability of specific (usually growth‑promoting) mRNAs 2.

- Nucleotide synthesis: promoting the synthesis of purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis both via activation of the pentose phosphate pathway and promoting folate flux via ATF4-dependent transcriptional activation. There is also evidence of mTORC1–S6K–CAD–mediated activation of de novo pyrimidine synthesis and mTORC1‑dependent regulation of SAM synthesis (the major methyl donor required for nucleotide synthesis) via Myc-dependent transcriptional activation of MAT2A 3.

- Lipid synthesis: activating SREBP1c to promote de novo lipogenesis and triglyceride synthesis. A recent paper also shows that cholesterol biosynthesis is promoted via USP20 dependent stabilization of HMGCR, the rate limiting enzyme of cholesterol synthesis 14.

- Glycogen synthesis: mTORC1 activation causes induction of the protein phosphatase 1 targetting subunits PTG4 and PPP1R3B5. The resultant dephosphorylation and activation of glycogen synthase (and inactivation of glycogen phosphorylase) promotes glycogen accumulation in vitro.

- Preventing autophagy: The catabolism of proteins via autophagy is also strongly attenuated by mTORC1 activity, in part by phosphorylation of ULK1 and Atg13 as well as TFEB inhibition, causing transcriptional downregulation of autophagic genes. In this way mTORC1 functions to prevent protein catabolism.

What these anabolic processes have in common is that they are all dependent on the presence of available nutrients (amino acids, folates, fatty acids) as well as are all generally energetically costly. Notably in all of these circumstances, these nutrients are effectively consumed or stored. Let's now review some of the key mTORC1-dependent nutrient consuming processes.

The dissipation of nutrients is driven by mTORC1

Promoting anabolic function alone would be predicted to cause nutrient dissipation, as amino acids, fatty acids, glucose and micronutrients are stored as macromolecules. However, in addition to that anabolic depletion, there is considerable evidence that, paradoxically, these nutrients are also catabolized in states of mTORC1 activation.

Amino acid oxidation is promoted by mTORC1 activation

The two most relevant steps for amino acid catabolism are glutamate catabolism into $\alpha$-ketoglutarate (several amino acids are catabolised via transaminases into glutamate and a carbon skeleton) and the resulting ammonia detoxification by the urea cycle. Glutamine is a store of amino groups that can then be used for non-essential amino acid biosynthesis. Two publications report the activation of glutaminolysis and glutamate oxidation in mTORC1-activated cells 6 7, though the later has since been retracted. mTORC1 inhibition by rapamycin also causes reduced activity of BCKDH, the rate limiting step of BCAA catabolism, consistent with a positive role of mTORC1 in BCAA oxidation 8 9.

Glycolysis is promoted via mTORC1-dependent HIF1 activation

mTORC1 promotes skeletal muscle fuel oxidation.

In muscle tissue, mTORC1 is activated by obesity @Khamzina2005b @Tremblay2007, concordant with a switch towards oxidative muscle fibers @Lexell1995a @Goodpaster2001 @Dube2008. Cell and animal models of mTORC1 activation have been developed via deletion of its negative regulators TSC1 and TSC2. These studies show that mTORC1 activation is sufficient for mitochondrial biogenesis, ATP production and whole-body energy expenditure @Cunningham2007 @Ramanathan2009 @Koyanagi2011 @Bentzinger2013 @Guridi2015.

Ketone body disposal is enhanced in mTORC1-activated muscle tissues

Ketogenesis is an alternative catabolic pathway for excessive fatty acids. In our model, we would predict that under chronic mTORC1 activation in liver we would observe increased ketone body production and that would be dissipated in ketolytic tissues. Indeed we do observe more rapid ketone body clearance in muscle Tsc1 knockout mice 10. Where things are less straightforward is in the ketogenesis step, where there are conflicting data whether liver Tsc1 knockout does 11 12 or does not 13 suppresses fasting ketone body levels.

mTORC1 as an Engine of Diet-Induced Thermogenesis

Increased energy expenditure is a normal physiologic mechanism to compensate for elevated caloric intake.

Clinical studies have shown that energy expenditure can adjust to under- or overfeeding @Acheson1988 @Leibel1995a. This is consistent with the observation that obese individuals have higher energy expenditure than lean subjects @James1978 @Ravussin1982 @Ravussin1986 @Leibel1995a @Delany2013. This process of diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) is an adaptation to higher macronutrient levels and functions to limit weight gain. In a small human study, acute suppression of energy expenditure by induced by fasting was inversely associated with the ability to lose weight on chronic calorie restriction @Meng2020. This suggests that diet-related adaptive thermogenesis may be more prognostic than the association between basal metabolic rate and obesity risk, which is minimal @Luke2009 @Rimbach2022. The mechanisms underlying DIT are largely unclear, but previous studies have shown that impairment of MC4R or β-adrenergic signaling blocks DIT @Rothwell1979 @Butler2001 @Bachman2002 @Berglund2014. We have shown that mTORC1 activity is necessary for diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) and is sufficient for increased energy expenditure and resistance to diet-induced obesity and metabolic disease.

Thermogenesis in Brown Adipose Tissue

Several papers demonstrate a role for mTORC1 in promoting BAT thermogenesis @Liu2016b @Labbe2016 @Lee2016a @Tran2016 @Magdalon2016,

Why do mouse models of mTORC1 activation typically appear as catabolic?

Intracellular scarsity and suppression of conservatory mechanisms

In this framing, mTORC1 causes a nutrient dissipation flux. In normal cells, a drop in nutrients would inhibit mTORC1, which then acts as a circuit breaker to this flux. However, in constitutive models (e.g., TSC1/2, GATOR1, or Sestrin deletions, Rheb/Rag activation mutants, PRAS40 deletion), the circuit breaker is removed and nutrient dissipation continues. As such, even as internal nutrient concentrations ($[N]$) fall, the cell continues to drive protein and lipid synthesis and nutrient catabolism. This intracellular scarcity is a state of starvation in the midst of plenty; the cell has the machinery to grow, but the raw materials are being dissipated faster than they can be replenished.

Decreased efficiency of nutrient metabolism

Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance at a cellular level.

The enhanced export of nutrients in models of mTORC1 activation

mTORC1 activation models cause reduced, not enhanced liver fat

Just as mTORC1 promotes the synthesis of cholesterol and lipids via the USP20–HMGCR axis 14, it simultaneously coordinates their export in the form of VLDL. In spite of an anabolic framing of lipid levels in the liver, Tsc1 knockout livers can clear hepatic lipid stores despite high synthetic rates.

Lactation and Nutrient Delivery

Similarly, in the mammary gland, this drive supports the high-flux delivery of nutrients during lactation.

Managing the boundaries of an open system

Metabolism is, of course, not a closed system. How should the organism respond if mTORC1 activity promotes both the dissipation and storage of nutrients? We posit that the same processes (potential scarcity from local nutrient dissipation) signal to paradoxically increase nutrient intake and absorption.

Effects on Appetite and Energy Intake

Role of mTORC1 on Nutrient Absorption

If this About Nutrient Excess, and if so which nutrients?

Implications

Leveraging nutrient dissipation for cancer growth

How does this square with mTORC1's effects on immune function

Aging and Chronic Disease

References

-

Ben-Sahra, Issam, and Brendan D. Manning. 2017. “mTORC1 Signaling and the Metabolic Control of Cell Growth.” Current Opinion in Cell Biology 45:72–82. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2017.02.012. ↩

-

Meyer, Kate D., and Samie R. Jaffrey. 2014. “The Dynamic Epitranscriptome: N6-Methyladenosine and Gene Expression Control.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 15(5):313–26. doi:10.1038/nrm3785. ↩

-

Villa, Elodie, Umakant Sahu, Brendan P. O’Hara, Eunus S. Ali, Kathryn A. Helmin, John M. Asara, Peng Gao, Benjamin D. Singer, and Issam Ben-Sahra. 2021. “mTORC1 Stimulates Cell Growth through SAM Synthesis and m6A mRNA-Dependent Control of Protein Synthesis.” Molecular Cell 81(10):2076-2093.e9. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.009. ↩

-

Lu, B., Dave Bridges, Y. Yang, K. Fisher, A. Cheng, L. Chang, Z. X. Meng, J. D. Lin, M. Downes, R. T. Yu, C. Liddle, R. M. Evans, and A. R. Saltiel. 2014. “Metabolic Crosstalk: Molecular Links between Glycogen and Lipid Metabolism in Obesity.” Diabetes 63(9). doi:10.2337/db13-1531. ↩

-

Uehara, Kahealani, Won Dong Lee, Megan Stefkovich, Dipsikha Biswas, Dominic Santoleri, Anna Garcia Whitlock, William Quinn, Talia Coopersmith, Kate Townsend Creasy, Daniel J. Rader, Kei Sakamoto, Joshua D. Rabinowitz, and Paul M. Titchenell. 2024. “mTORC1 Controls Murine Postprandial Hepatic Glycogen Synthesis via Ppp1r3b.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation 134(7):e173782. doi:10.1172/JCI173782. ↩

-

Csibi, Alfredo, Gina Lee, Sang Oh Yoon, Haoxuan Tong, Didem Ilter, Ilaria Elia, Sarah Maria Fendt, Thomas M. Roberts, and John Blenis. 2014. “The mTORC1/S6K1 Pathway Regulates Glutamine Metabolism through the Eif4b-Dependent Control of c-Myc Translation.” Current Biology 24(19):2274–80. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.007. ↩

-

Csibi, Alfred, Sarah-Maria Fendt, Chenggang Li, George Poulogiannis, Andrew Y. Choo, Douglas J. Chapski, Seung Min Jeong, Jamie M. Dempsey, Andrey Parkhitko, Tasha Morrison, Elizabeth Petri Henske, Marcia C. Haigis, Lewis C. Cantley, Gregory Stephanopoulos, Jane Yu, and John Blenis. 2013. “The mTORC1 Pathway Stimulates Glutamine Metabolism and Cell Proliferation by Repressing SIRT4.” Cell 153(4):840–54. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.023. ↩

-

Zhen, Hongmin, Yasuyuki Kitaura, Yoshihiro Kadota, Takuya Ishikawa, Yusuke Kondo, Minjun Xu, Yukako Morishita, Miki Ota, Tomokazu Ito, and Yoshiharu Shimomura. 2016. “mTORC1 Is Involved in the Regulation of Branched‐chain Amino Acid Catabolism in Mouse Heart.” FEBS Open Bio 6(1):43–49. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12007. ↩

-

Neishabouri, S. Hallaj, S. M. Hutson, and J. Davoodi. 2015. “Chronic Activation of mTOR Complex 1 by Branched Chain Amino Acids and Organ Hypertrophy.” Amino Acids 47(6):1167–82. doi:10.1007/s00726-015-1944-y. ↩

-

Cousineau, Cody M., Detrick Snyder, JeAnna R. Redd, Sophia Turner, Treyton Carr, and Dave Bridges. 2024. “Reduced Beta-Hydroxybutyrate Disposal after Ketogenic Diet Feeding in Mice.” BioR$\Chi$ivdoi:10.1101/2024.05.16.594369. ↩

-

Sengupta, Shomit, Timothy R. Peterson, Mathieu Laplante, Stephanie Oh, and David M. Sabatini. 2010. “MTORC1 Controls Fasting-Induced Ketogenesis and Its Modulation by Ageing.” Nature 468(7327):1100–1106. doi:10.1038/nature09584. ↩

-

Kucejova, Blanka, Joao Duarte, Santhosh Satapati, Xiaorong Fu, Olga Ilkayeva, Christopher B. Newgard, James Brugarolas, and Shawn C. Burgess. 2016. “Hepatic mTORC1 Opposes Impaired Insulin Action to Control Mitochondrial Metabolism in Obesity.” Cell Metabolism 16(2):508–19. https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/abstract/S2211-1247(16)30725-2. ↩

-

Ebru S., and Michael J. Wolfgang. 2021. “mTORC1 Activation Is Not Sufficient to Suppress Hepatic PPARα Signaling or Ketogenesis.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry 297(1):178–83. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100884. ↩

-

Lu, Xiao-Yi, Xiong-Jie Shi, Ao Hu, Ju-Qiong Wang, Yi Ding, Wei Jiang, Ming Sun, Xiaolu Zhao, Jie Luo, Wei Qi, and Bao-Liang Song. 2020. “Feeding Induces Cholesterol Biosynthesis via the mTORC1–USP20–HMGCR Axis.” Nature 588(7838):479–84. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2928-y. ↩↩

Comments